As always, dictionary definition first:

visibility

n.

1. the condition or fact of being visible

2. clarity of vision or relative possibility of seeing

3. the range of vision visibility is 500 yards

Calvino began his memo on Visibility by asserting that, “fantasy is a place where it rains,” swiftly flowing into a brief discussion of imagination in the abstract. He said that imagination is a sort of “high fantasy” that works in special ways, beyond the scientific study of the mind. To give us an understanding of imagination, he paraphrased Dante’s Purgatorio saying,

“O imagination, you who have the power to impose yourself on our faculties and our wills, stealing us away from the outer world and carrying us off into an inner one, so that even if a thousand trumpets were to sound we would not hear them, what is the source of the visual messages that you receive, if they are not formed from sensations deposited in the memory?”

This raised the question of where the images that often flash before our eyes come from…a recurring pondering in this memo.

Calvino proceeded to discuss another work by Dante, Commedia, to further his own position on comparing imagination to cinema and of visions being presented like film projections or television images seen on a screen. In cinema, the image we ultimately see on screen derives from a written text (the screenplay). This text has been “visualized” by a director, reconstructed by way of the set, costuming, etc., and is finally secured within the frames of the film itself.

Calvino proceeded to discuss another work by Dante, Commedia, to further his own position on comparing imagination to cinema and of visions being presented like film projections or television images seen on a screen. In cinema, the image we ultimately see on screen derives from a written text (the screenplay). This text has been “visualized” by a director, reconstructed by way of the set, costuming, etc., and is finally secured within the frames of the film itself.

In a way, imagination is very much like cinema…it’s a “mental cinema.” The way we record memories as sequences is similar to that of the camera. However, while movies ultimately end, mental cinema is constant and infinite.

Calvino explained that there are two types of imaginative processes,

- The first starts with the word and arrives at the visual image

- The second starts with the visual image and arrives at verbal expression

and he questioned which of these processes is superior, comparing this conundrum to the age-old problem of the chicken and the egg.

What vision is produced before our eyes or inside our minds when we read any text?

To illustrate the struggle, he referenced Douglas Hofstadter’s writing in Gödel, Escher, Bach,

“Think, for instance, of a writer who is trying to convey certain ideas which to him are contained in mental images. He isn’t quite sure how those images fit together in his mind, and he experiments around, expressing things first one way and then another, and finally settles on some version. But does he know where it all came from? Only in a vague sense. Much of the source, like an iceberg, is deep underwater, unseen—and he knows that.”

Finally, Calvino divulged his own tendencies and experiences as a writer, especially in writing “fantastic stories.” He had always recognized a visual image as the source for all his stories, providing a few driving examples:

- A man cut in two halves, each of which went on living independently

- A boy who climbs a tree and then makes his way from tree to tree without ever coming down to earth

- An empty suit of armor that moves and speaks as if someone were inside

Such images, he said, are charged with meaning.

“As soon as the image has become sufficiently clear in my mind, I set about developing it into a story; or better yet, it is the images themselves that develop their own implicit potentialities, the story they carry within them. Around each image others come into being, forming a field of analogies, symmetries, confrontations.”

Calvino proceeded to reveal that, while the visual image was initially dominant, the word ultimately takes over. After he searched for words that seemed to be equivalent to and illustrative of the image in his mind, he allowed the words to drive the rest of the story.

As in all of his memos, Calvino explained why visibility is such a significant value in today’s day and age. He feared that the human faculty of “the power of bringing visions into focus with our eyes shut, of bringing forth forms and colors from the lines of black letters on a white page and, in fact, of thinking in terms of images,” might be lost. In expressing his fear, I believe that Calvino touched upon the ultimate definition of visibility. Today, with the number of images out there, there’s much less left to the imagination and people are seemingly less creative than they once were.

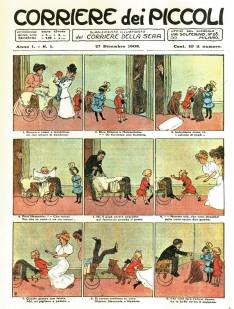

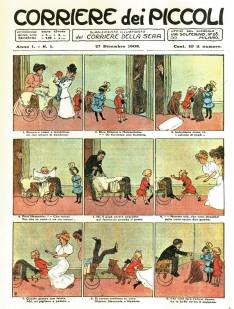

Comic from Corriere dei piccoli without speech bubbles

While today children are given a “Game Boy” to play with, Calvino reminisced upon his own “childhood companions,” most notably American comic strips published in the Corriere de piccolo. In those comics, there weren’t balloons for dialogue, just a few explanatory lines under the cartoons. Regardless, Calvino couldn’t yet read. Thus, he had to take the images and produce his own meaning:

“In my mind I told myself the stories, interpreting the scenes in different ways, I produced variants, put together the single episode into a story of broader scope, thought out and isolated and then connected the recurring elements in each series, mixing up one series with another, and invented new series in which the secondary characters became protagonists.”

Such activities yielded to the formation of a habit for Calvino—to concentrate on images rather than written words.

Finally, Calvino attempted to answer the recurring question of where our mental “database” of images comes from:

“Let us say that various elements concur in forming the visual part of the literary imagination: direct observation of the real world, phantasmic and oneiric transfiguration, the figurative world as it is transmitted by culture at its various levels, and a process of abstraction, condensation, and interiorization of sense experience, a matter of prime importance to both the visualization and the verbalization of thought.”

Truffaut’s “Shoot the Piano Player”

With much discussion of cinema throughout this memo, it’s no surprise that François Truffaut was on my mind. An influential director, screenwriter, producer, actor, and film critic, Truffaut has played a huge role in shaping the history of film. However, there is a more significant reason that he seems so relevant to the issue of visibility. In a discussion of his 1960 crime-drama, Shoot the Piano Player, a film about a washed-up piano player who suffers great loss and encounters difficulty with gangsters, Truffaut once said,

“For Shoot the Piano Player, which is adapted from a novel by David Goodis, a single image made me decide to make the film. It was in the book. A sloping road in the snow, the car running down it with no noise from the motor. That’s all. The image of a car gliding through the snow with no noise from the motor, that was something I wanted terribly to visualize, and all the rest followed…”

Still from “Shoot the Piano Player” (car on snowy slope)

In watching the film, it’s clear just how deeply that image affected Truffaut’s vision. This literally embodies the first imaginative process described by Calvino (starting with the word, arriving at the visual image). What Truffaut read in the original novel became a mental image which he ultimately transposed onto the screen, for all to see. In the film, snow-covered slopes play an essential role, adding to the pathos of many scenes.

Still from “Shoot the Piano Player” (Lena, dead in the snow)

Originally I was set on using filmmaking as my analogy for Visibility. It seemed perfect. An initial story or idea goes through multiple phases—some verbal and others visual—from storyboarding and scriptwriting, to casting, shooting, editing, and finally screening. However, Calvino really had already used cinema as an analogy for visibility. Thus, I’m turning to a product of the art of filmmaking—one of my favorite movies, Ruby Sparks. The film centers on a writer and perpetual loner named Calvin (Paul Dano) who is suffering from writer’s block. Finally, as a project given to him by his therapist, he sits down at his manual (and perhaps magical) typewriter and begins to write his dream girl, Ruby Sparks (Zoe Kazan), into fictional existence:

Originally I was set on using filmmaking as my analogy for Visibility. It seemed perfect. An initial story or idea goes through multiple phases—some verbal and others visual—from storyboarding and scriptwriting, to casting, shooting, editing, and finally screening. However, Calvino really had already used cinema as an analogy for visibility. Thus, I’m turning to a product of the art of filmmaking—one of my favorite movies, Ruby Sparks. The film centers on a writer and perpetual loner named Calvin (Paul Dano) who is suffering from writer’s block. Finally, as a project given to him by his therapist, he sits down at his manual (and perhaps magical) typewriter and begins to write his dream girl, Ruby Sparks (Zoe Kazan), into fictional existence: However, her existence turns out to not be quite so fictional. The next day, he comes home only to learn that Ruby has become a real person and that everything he had written about her is fact. After getting over the initial shock, Calvin comes to terms with the reality of his situation and he and Ruby begin to truly enjoy their relationship and fall deeply in love. However, Calvin soon discovers that his ability to write things into reality wasn’t a one-time thing. He can continue to write and change Ruby if she isn’t acting the way he wants her to behave. He can change how she looks, thinks, feels, acts, and even speaks (even writing her the ability to speak French at one point in the film), which comes in handy for him when he sees that their relationship is going downhill. (I would tell you more, but I don’t want to spoil the ending!)

However, her existence turns out to not be quite so fictional. The next day, he comes home only to learn that Ruby has become a real person and that everything he had written about her is fact. After getting over the initial shock, Calvin comes to terms with the reality of his situation and he and Ruby begin to truly enjoy their relationship and fall deeply in love. However, Calvin soon discovers that his ability to write things into reality wasn’t a one-time thing. He can continue to write and change Ruby if she isn’t acting the way he wants her to behave. He can change how she looks, thinks, feels, acts, and even speaks (even writing her the ability to speak French at one point in the film), which comes in handy for him when he sees that their relationship is going downhill. (I would tell you more, but I don’t want to spoil the ending!)